- Home

- Wallis, Velma

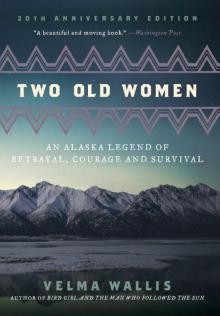

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival Read online

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to all of the elders whom I have known and who have made an impression in my mind with their wisdom, knowledge and uniqueness.

Mae P. Wallis, Mary Hardy, Dorothy Earls, Sarah Gottschalk, Ida Neyhart, Patricia Peters, Edison Peters, Helen Reed, Moses Peter, Martha Wallis, Louise Paul, Minnie Salmon, Lilly Herbert, David and Sarah Salmon, Samson and Minnie Peter, Herbert and Louise Peter, Stanley and Rosalie Joseph, Margaret John, Paul and Margaret Williams, Leah Roberts, Natalie Erick, Daniel Horace, Titus Peter, Solomon and Martha Flitt, Doris Ward, Amos Kelly, Margaret Kelly, Maggie Beach, Sarah Alexander, Peter and Nina (Ch’idzigyaak) Joseph, Paul and Agnes James, Mariah Collins, David Collins, Mary Thompson, Sophie Williams, Elijah John, Jemima Fields, Ike Fields Sr., Joe and Margaret Carroll, Myra Francis, Blanche Strom, Arthur and Annie James, Elliot and Lucy Johnson, Elliot and Virginia Johnson II,

Harry and Jessie Carroll, Margaret Cadzow, Henry and Jennie Williams, Issac and Sarah John, Charlotte Douthit, Ruth Martin, Randall Baalam, Harold and Ester Petersen, Vladimer and Nina Petersen, Addie Shewfelt, Stanley and Madeline Jonas, Jonathon and Hannah Solomon, Esau and Delia Williams, Margie Englishoe, Jessie Luke, Julia Peter, Jacob Flitt, Daniel and Nina Flitt, Clara Gundrum, Jessie Williams, Sarah W. John, Mary Simple, Ellen Henry, Silas John, Dan Frank, Maggie Roberts, Nina Roberts, Abraham and Annie Christian, Paul and Julia Tritt, Agnes Peter, Charlie Peter, Neil and Sarah Henry, Mardow Solomon, Ruth Peterson, Phillip and Abbie Peter,

Archie and Louise Juneby, Harry and Bessie David, Margaret Roberts, John Stevens, Steven and Sarah Henry, Abel Tritt, Moses and Jennie Sam, Mary John, Martha James, Alice Peter, Nathanial and Annie Frank, Fred and Charlotte Thomas, Richard and Eva Carroll, Elsie Pitka, Richard and Helen Martin, Paul Gabrial, Grafton Gabrial, Barbara Solomon, Sabastian McGinty, Simon and Bella Francis, Mary Jane Alexander, and Uncle Lee Henry.

CONTENTS

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Introduction

CHAPTER 1: Hunger and cold take their toll

CHAPTER 2: “Let us die trying”

CHAPTER 3: Recalling old skills

CHAPTER 4: A painful journey

MAP

CHAPTER 5: Saving a cache of fish

CHAPTER 6: Sadness among The People

CHAPTER 7: The stillness is broken

CHAPTER 8: A new beginning

About the Gwich’in People

About the Authors

Back Ad

Praise

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Most artists can say that if it were not for a number of people he or she would not have achieved a certain success. In the case of this story and myself, the list is long and varied and I would like to acknowledge them as follows.

First, thank you to my mother, Mae Wallis. Without you, this story would not be, and I never would have developed a desire to be a storyteller. All those many nights that you spent telling us stories are greatly appreciated.

I would like to thank these people for believing in this story all these years, and for reviving it just when I thought it would sink back into oblivion: Barry Wallis, Marti Ann Wallis, Patricia Stanley, and Carroll Hodge; Judy Erick from Venetie for her flexible assistance with the Gwich’in translations and Annette Seimens for letting me use her computer.

Last, I would like to thank Marilyn Savage for her generosity and persistent rallying. Thank you to the publishers, Kent Sturgis and Lael Morgan, for sharing the same vision as all of us. Thank you to Virigina Sims for making sure that the story remained the same with your editing, and to James Grant for making the characters come to life with your talented illustrations.

Mahsi Choo to each and all of you for sharing in this humble story.

INTRODUCTION

Each day after cutting wood we would sit and talk in our small tent on the bank at the mouth of the Porcupine River, near where it flows into the Yukon. We would always end with Mom telling me a story. (There I was, long past my youth, and my mother still told me bedtime stories!) One night it was a story I heard for the first time—a story about two old women and their journey through hardship.

What brought the story to mind was a conversation we had earlier while working side by side collecting wood for the winter. Now we sat on our bedrolls and marveled at how Mom in her early fifties still was able to do this kind of hard work while most people of her generation long since had resigned themselves to old age and all of its limitations. I told her I wanted to be like her when I became an elder.

We began to remember how it once was. My grandmother and all those other elders from the past kept themselves busy until they could no longer move or until they died. Mom felt proud that she was able to overcome some of the obstacles of old age and still could get her own winter wood despite the fact that physically, the work was difficult and sometimes agonizing. During our pondering and reflections, Mom remembered this particular story because it was appropriate to all that we thought and felt at that moment.

Later, at our winter cabin, I wrote the story down. I was impressed with it because it not only taught me a lesson that I could use in my life, but also because it was a story about my people and my past—something about me that I could grasp and call mine. Stories are gifts given by an elder to a younger person. Unfortunately, this gift is not given, nor received, as often today because many of our youth are occupied by television and the fast pace of modern-day living. Maybe tomorrow a few of today’s generation who were sensitive enough to have listened to their elders’ wisdom will have the traditional word-of-mouth stories living within their memory. Perhaps tomorrow’s generation also will yearn for stories such as this so that they may better understand their past, their people and, hopefully, themselves.

Sometimes, too, stories told about one culture by someone from another way of life are misinterpreted. This is tragic. Once set down on paper, some stories are readily accepted as history, yet they may not be truthful.

This story of the two old women is from a time long before the arrival of the Western culture, and has been handed down from generation to generation, from person to person, to my mother, and then to me. Although I am writing it, using a little of my own creative imagination, this is, in fact, the story I was told and the point of the story remains the way Mom meant for me to hear it.

This story told me that there is no limit to one’s ability—certainly not age—to accomplish in life what one must. Within each individual on this large and complicated world there lives an astounding potential of greatness. Yet it is rare that these hidden gifts are brought to life unless by the chance of fate.

CHAPTER 1

Hunger and cold take their toll

The air stretched tight, quiet and cold over the vast land. Tall spruce branches hung heavily laden with snow, awaiting distant spring winds. The frosted willows seemed to tremble in the freezing temperatures.

Far off in this seemingly dismal land were bands of people dressed in furs and animal skins, huddled close to small campfires. Their weather-burnt faces were stricken with looks of hopelessness as they faced starvation, and the future held little promise of better days.

These nomads were The People of the arctic region of Alaska, always on the move in search of food. Where the caribou and other migrating animals roamed, The People followed. But the deep cold of winter presented special problems. The moose, their favorite source of food, took refuge from the penetrating cold by staying in one place, and were diffic

ult to find. Smaller, more accessible animals such as rabbits and tree squirrels could not sustain a large band such as this one. And during the cold spells, even the smaller animals either disappeared in hiding or were thinned by predators, man and animal alike. So during this unusually bitter chill in the late fall, the land seemed void of life as the cold hovered menacingly.

During the cold, hunting required more energy than at other times. Thus, the hunters were fed first, as it was their skills on which The People depended. Yet, with so many to feed, what food they had was depleted quickly. Despite their best efforts, many of the women and children suffered from malnutrition, and some would die of starvation.

In this particular band were two old women cared for by The People for many years. The older woman’s name was Ch’idzigyaak, for she reminded her parents of a chickadee bird when she was born. The other woman’s name was Sa’, meaning “star,” because at the time of her birth her mother had been looking at the fall night sky, concentrating on the distant stars to take her mind away from the painful labor contractions.

The chief would instruct the younger men to set up shelters for these two old women each time the band arrived at a new campsite, and to provide them with wood and water. The younger women pulled the two elder women’s possessions from one camp to the next and, in turn, the old women tanned animal skins for those who helped them. The arrangement worked well.

However, the two old women shared a character flaw unusual for people of those times. Constantly they complained of aches and pains, and they carried walking sticks to attest to their handicaps. Surprisingly, the others seemed not to mind, despite having been taught from the days of their childhood that weakness was not tolerated among the inhabitants of this harsh motherland. Yet, no one reprimanded the two women, and they continued to travel with the stronger ones—until one fateful day.

On that day, something more than the cold hung in the air as The People gathered around their few flickering fires and listened to the chief. He was a man who stood almost a head taller than the other men. From within the folds of his parka ruff he spoke about the cold, hard days they were to expect and of what each would have to contribute if they were to survive the winter.

Then, in a loud, clear voice he made a sudden announcement: “The council and I have arrived at a decision.” The chief paused as if to find the strength to voice his next words. “We are going to have to leave the old ones behind.”

His eyes quickly scanned the crowd for reactions. But the hunger and cold had taken their toll, and The People did not seem to be shocked. Many expected this to happen, and some thought it for the best. In those days, leaving the old behind in times of starvation was not an unknown act, although in this band it was happening for the first time. The starkness of the primitive land seemed to demand it, as the people, to survive, were forced to imitate some of the ways of the animals. Like the younger, more able wolves who shun the old leader of the pack, these people would leave the old behind so that they could move faster without the extra burden.

The older woman, Ch’idzigyaak, had a daughter and a grandson among the group. The chief looked into the crowd for them and saw that they, too, had shown no reaction. Greatly relieved that the unpleasant anouncement had been made without incident, the chief instructed everyone to pack immediately. Meanwhile, this brave man who was their leader could not bring himself to look at the two old women, for he did not feel so strong now.

The chief understood why The People who cared for the old women did not raise objections. In these hard times, many of the men became frustrated and were angered easily, and one wrong thing said or done could cause an uproar and make matters worse. So it was that the weak and beaten members of the tribe kept what dismay they felt to themselves, for they knew that the cold could bring on a wave of panic followed by cruelty and brutality among people fighting for survival.

In the many years the women had been with the band, the chief had come to feel affection for them. Now, he wanted to be away as quickly as possible so that the two old women could not look at him and make him feel worse than he had ever felt in his life.

The two women sat old and small before the campfire with their chins held up proudly, disguising their shock. In their younger days they had seen very old people left behind, but they never expected such a fate. They stared ahead numbly as if they had not heard the chief condemn them to a certain death—to be left alone to fend for themselves in a land that understood only strength. Two weak old women stood no chance against such a rule. The news left them without words or action and no way to defend themselves.

Of the two, Ch’idzigyaak was the only one with a family—a daughter, Ozhii Nelii, and a grandson, Shruh Zhuu. She waited for her daughter to protest, but none came, and a deeper sense of shock overcame her. Not even her own daughter would try to protect her. Next to her, Sa’ also was stunned. Her mind reeled and, though she wanted to cry out, no words came. She felt as if she were in a terrible nightmare where she could neither move nor speak.

As the band slowly trudged away, Ch’idzigyaak’s daughter went over to her mother, carrying a bundle of babiche—thickly stripped raw moosehide that served many purposes. She hung her head in shame and grief, for her mother refused to acknowledge her presence. Instead, Ch’idzigyaak stared unflinchingly ahead.

Ozhii Nelii was in deep turmoil. She feared that, if she defended her mother, The People would settle the matter by leaving her behind and her son, too. Worse yet, in their famished state, they might do something even more terrible. She could not chance it.

With those frightening thoughts, Ozhii Nelii silently begged with sorrowful eyes for forgiveness and understanding as she gently laid the babiche down in front of her rigid parent. Then she slowly turned and walked away with a heaviness in her heart, knowing she had just lost her mother.

The grandson, Shruh Zhuu, was deeply disturbed by the cruelty. He was an unusual boy. While the other boys competed for their manhood by hunting and wrestling, this one was content to help provide for his mother and the two old women. His behavior seemed to be outside of the structure of the band’s organization handed down from generation to generation. In this case, the women did most of the burdensome tasks such as pulling the well-packed toboggans. In addition, much other time-consuming work was expected to be done by the women while the men concentrated on hunting so that the band could survive. No one complained, for that was the way things were and always had been.

Shruh Zhuu held much respect for the women. He saw how they were treated and he disapproved. And while it was explained to him over and over, he never understood why the men did not help the women. But his training told him that he never was to question the ways of The People, for that would be disrespectful. When he was younger, Shruh Zhuu was not afraid to voice his opinions on this subject, for youth and innocence were his guardians. Later, he learned that such behavior invited punishment. He felt the pain of the silent treatment when even his mother refused to speak to him for days. So Shruh Zhuu learned that it caused less pain to think about certain things than to speak out about them.

Although he thought abandoning the helpless old women was the worst thing The People could do, Shruh Zhuu was struggling with himself. His mother saw the turmoil raging in his eyes and she knew that he was close to protesting. She went to him quickly and whispered urgently into his ear not to think of it, for the men were desperate enough to commit any kind of cruel action. Shruh Zhuu saw the men’s dark faces and knew this to be true, so he held his tongue even as his heart continued to rage rebelliously.

In those days, each young boy was trained to care for his weapons, sometimes better than he cared for his loved ones, for the weapons were to be his livelihood when he became a man. When a boy was caught handling his weapon the wrong way or for the wrong purpose, it resulted in harsh punishment. As he grew older, the boy would learn the power of his weapon and how much significance it had, not only for his own survival but also for that of his people.

Shruh Zhuu threw all this training and thoughts of his own safety to the winds. He took from his belt a hatchet made of sharpened animal bones bound tightly together with hardened babiche and stealthily placed it high in the thick boughs of a bushy young spruce tree, well concealed from the eyes of The People.

As Shruh Zhuu’s mother packed their things, he turned toward his grandmother. Though she seemed to look right through him, Shruh Zhuu made sure no one was watching as he pointed to his empty belt, then toward the spruce tree. Once more he gave his grandmother a look of hopelessness, and reluctantly turned and walked away to join the others, wishing with a sinking feeling that he could do something miraculous to end this nightmarish day.

The large band of famished people slowly moved away, leaving the two women sitting in the same stunned position on their piled spruce boughs. Their small fire cast a soft orange glow onto their weathered faces. A long time passed before the cold brought Ch’idzigyaak out of her stupor. She was aware of her daughter’s helpless gesture but believed that her only child should have defended her even in the face of danger. The old woman’s heart softened as she thought of her grandson. How could she bear hard feelings toward one so young and gentle? The others made her angry, especially her daughter! Had she not trained her to be strong? Hot, unbidden tears ran from her eyes.

At that moment, Sa’ lifted her head in time to see her friend’s tears. A rush of anger surged within her. How dare they! Her cheeks burned with the humiliation. She and the other old woman were not close to dying! Had they not sewed and tanned for what the people gave them? They did not have to be carried from camp to camp. They were neither helpless nor hopeless. Yet they had been condemned to die.

Her friend had seen eighty summers, she, seventy-five. The old ones she had seen left behind when she was young were so close to death that some were blind and could not walk. Now here she was, still able to walk, to see, to talk, yet . . . bah! Younger people these days looked for easier ways out of hard times. As the cold air smothered the campfire, Sa’ came alive with a greater fire within her, almost as if her spirit had absorbed the energy from the now-glowing embers of the campfire. She went to the tree and retrieved the hatchet, smiling softly as she thought of her friend’s grandson. She sighed as she walked toward her companion, who had not stirred.

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival