- Home

- Wallis, Velma

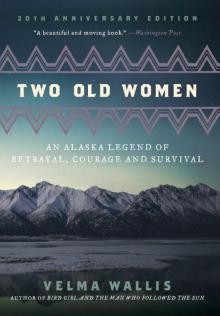

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival Page 2

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival Read online

Page 2

Sa’ looked up at the blue sky. To an experienced eye, the blue this time of winter meant cold. Soon it would be colder yet as night approached. With a worried frown on her face, Sa’ kneeled beside her friend and spoke in a gentle but firm voice. “My friend,” she said and paused, hoping for more strength than she felt. “We can sit here and wait to die. We will not have long to wait . . .

“Our time of leaving this world should not come for a long time yet,” she added quickly when her friend looked up with panic-stricken eyes. “But we will die if we just sit here and wait. This would prove them right about our helplessness.”

Ch’idzigyaak listened with despair. Knowing that her friend was dangerously close to accepting a fate of death from cold and hunger, Sa’ spoke more urgently. “Yes, in their own way they have condemned us to die! They think that we are too old and useless. They forget that we, too, have earned the right to live! So I say if we are going to die, my friend, let us die trying, not sitting.”

CHAPTER 2

“Let us die trying”

Ch’idzigyaak sat quietly as if trying to make up her confused mind. A small feeling of hope sparked in the blackness of her being as she listened to her friend’s strong words. She felt the cold stinging her cheeks where her tears had fallen, and she listened to the silence that The People left behind. She knew that what her friend said was true, that within this calm, cold land waited a certain death if they did nothing for themselves. Finally, more in desperation than in determination she echoed her friend’s words, “Let us die trying.” With that, her friend helped her up off the sodden branches.

The women gathered sticks to build the fire and they added pieces of fungus that grew large and dry on fallen cottonwood trees to keep it smoldering. They went around to other campfires to salvage what embers they could find. As they packed to travel, the migrating bands in these times preserved hot coals in hardened mooseskin sacks or birchbark containers filled with ash in which the embers pulsated, ready to spark the next campfire.

As night approached, the women cut thin strips from the bundle of babiche, fashioning them into nooses the size of a rabbit’s head. Then, despite their weariness, the women managed to make some rabbit snares, which they immediately set out.

The moon hung big and orange on the horizon as they trudged through the knee-deep snow, searching in the dimness for signs of rabbit life. It was hard to see, and what rabbits existed stayed quiet in the cold weather. But they found several old, hardened rabbit trails frozen solid beneath the trees and arching willows. Ch’idzigyaak tied a babiche noose to a long, thick willow branch and placed it across one of the trails. She made little fences of willows and spruce boughs on each side of the noose to guide the rabbit through the snare. The two women set a few more snares but felt little hope that even one rabbit would be caught.

On their way back to the camp, Sa’ heard something skitter lightly along the bark of a tree. She stood very still, motioning her friend to do the same. Both women strained to hear the sound once more in the silence of the night. On a tree not far from them, silhouetted in the now-silvery moonlight, they saw an adventurous tree squirrel. Sa’ slowly reached to her belt for the hatchet. With her eyes on the squirrel and her movements deliberately slow, she aimed the hatchet toward this target that represented survival. The animal’s small head came up instantly and as Sa’ moved her hand to throw, the squirrel darted up the tree. Sa’ foresaw this, and, aiming a little higher, ended the small animal’s life in one calculating throw with skill and hunting knowledge that she had not used in many seasons.

Ch’idzigyaak let out a deep sigh of relief. The moon’s light shone on the younger woman’s smiling face as she said in a proud yet shaky voice, “Many times I have done that, but never did I think I would do it again.”

Back at the camp, the women boiled the squirrel meat in snow water and drank the broth, saving the small portion of meat to be eaten later, for they knew that otherwise, this could be their last meal.

The two women had not eaten for some time because The People had tried to conserve what little food they had. Now they realized why precious food had not been given to them. Why waste food on two who were to die? Trying not to think about what had happened, the two women filled their empty stomachs with the warm squirrel broth and settled down in their tents for the night.

The shelter was made of two large caribou hides wrapped around three long sticks shaped into a kind of triangle. Inside were thickly piled spruce boughs covered with many fur blankets. The women were aware that, although they had been left behind to fend for themselves, The People had done them a good deed by leaving them with all their possessions. They suspected that the chief was responsible for this small kindness. Other less noble members of the band would have decided that the two women soon would die and would have pilfered everything except for the warm fur and skin clothing they wore. With these confusing thoughts lingering in their minds, the two frail women dozed.

The moonlight shone silently upon the frozen earth as life whispered throughout the land, broken now and then by a lone wolf’s melancholy howl. The women’s eyes twitched in tired, troubled dreams, and soft helpless moans escaped from their lips. Then a cry rang out somewhere in the night as the moon dipped low on the western horizon. Both women awoke at once, hoping that the awful screech was a part of her nightmare. Again the wail was heard. This time, the women recognized it as the sound of something caught in one of their snares. They were relieved. Fearing that other predators would beat them to their catch, the women hurriedly dressed and rushed to their snare sets. There they saw a small, trembling rabbit that lay partially strangled as it eyed them warily. Without hesitation, Sa’ went to the rabbit, put one hand around its neck, felt for the beating heart, and squeezed until the small struggling animal went limp. After Sa’ reset the snare, they went back to the camp, each feeling a thread of new hope.

Morning came, but brought no light to this far northern land. Ch’idzigyaak awoke first. She slowly kindled the fire into a flame as she carefully added more wood. When the fire had died out during the cold night, frost from their warm breathing had accumulated on the walls of caribou skins.

Sighing in dull exasperation, Ch’idzigyaak went outside where the northern lights still danced above, and the stars winked in great numbers. Ch’idzigyaak stood for a moment staring up at these wonders. In all her years, the night sky never failed to fill her with awe.

Remembering her task, Ch’idzigyaak grabbed the upper rims of the caribou skins, laid them on the ground and briskly brushed off the crystal frost. After putting the skins up again, she went back inside to build up the campfire. Soon moisture dripped from the skin wall, which quickly dried.

Ch’idzigyaak shuddered to think of the melting frost dripping on them in the cold weather. How had they managed before? Ah, yes! The younger ones were always there, piling wood on the fire, peering into the shelter to make sure that their elders’ fire did not go out. What a pampered pair they had been! How would they survive now?

Ch’idzigyaak sighed deeply, trying not to dwell on those dark thoughts, and concentrated instead on tending the fire without waking her sleeping companion. The shelter warmed as the fire crackled, spitting tiny sparks from the dry wood. Slowly, Sa’ awoke to this sound and lay on her back for a long time before becoming aware of her friend’s movement. Turning her aching neck slowly she began to smile but stopped as she saw her friend’s forlorn look. In a pained grimace Sa’ propped herself up carefully on one elbow and tried to smile encouragingly as she said, “I thought yesterday had only been a dream when I awoke to your warm fire.”

Ch’idzigyaak managed a slight smile at the obvious attempt to lift her spirits but continued to stare dully into the fire. “I sit and worry,” she said after a long silence. “I fear what lies ahead. No! Don’t say anything!” She held up her hands as her friend opened her mouth to speak.

“I know that you are sure of our survival. You are younger.” She could no

t help but smile bitterly at her remark, for just yesterday they both had been judged too old to live with the young. “It has been a long time since I have been on my own. There has always been someone there to take care of me, and now . . .” She broke off with a hoarse whisper as tears fell, much to her shame.

Her friend let her cry. As the tears eased and the older woman wiped her dampened face, she laughed. “Forgive me, my friend. I am older than you. Yet I cry like a baby.”

“We are like babies,” Sa’ responded. The older woman looked up in surprise at such an admission. “We are like helpless babies.” A smile twitched her lips as her friend started to look slightly affronted by the remark, but before Ch’idzigyaak could take it in the wrong way Sa’ went on. “We have learned much during our long lives. Yet there we were in our old age, thinking that we had done our share in life. So we stopped, just like that. No more working like we used to, even though our bodies are still healthy enough to do a little more than we expect of ourselves.”

Ch’idzigyaak sat listening, alert to her friend’s sudden revelation as to why the younger ones thought it best to leave them behind. “Two old women. They complain, never satisfied. We talk of no food, and of how good it was in our days when it really was no better. We think that we are so old. Now, because we have spent so many years convincing the younger people that we are helpless, they believe that we are no longer of use to this world.”

Seeing tears fill her friend’s eyes at the finality of her words, Sa’ continued in a voice heavy with feeling. “We are going to prove them wrong! The People. And death!” She shook her head, motioning into the air. “Yes, it awaits us, this death. Ready to grab us the moment we show our weak spots. I fear this kind of death more than any suffering you and I will go through. If we are going to die anyway, let us die trying!”

Ch’idzigyaak stared for a long time at her friend and knew that what she said was true, that death surely would come if they did not try to survive. She was not convinced that the two of them were strong enough to make it through the harsh season, but the passion in her friend’s voice made her feel a little better. So, instead of feeling sadness because there was nothing further they could say or do, she smiled. “I think we said this before and will probably say it many more times, but yes, let us die trying.” And with a sense of strength filling her like she had not thought possible, Sa’ returned the smile as she got up to prepare for the long day ahead of them.

CHAPTER 3

Recalling old skills

That day the women went back in time to recall the skills and knowledge that they had been taught from early childhood.

They began by making snowshoes. Usually birchwood was collected during late spring and early summer, but today the young birch would have to do. They didn’t have the correct tools, of course, but the women managed with what they had to split the wood into four parts each, which they boiled in their large birch containers. When the wood became soft, the women bent it roundish and pointed at the tips. Putting two of these half-rounded sides together, the women awkwardly drilled many little holes into both sides with their small pointed sewing awls. The work was hard, but despite their aching fingers the women continued until they finished the task. Earlier, they had soaked the babiche in water. Now they took the softened material, sliced it into thin strips, and wove it onto the snowshoes. As the babiche hardened with a little help from the campfire, the women prepared leather bindings for their snowshoes.

When they finished, the women beamed with pride. Then they walked atop the snow with their slightly awkward but serviceable snowshoes to check their rabbit snares and were further cheered to find they had caught another rabbit. The knowledge that a few days before The People had tried to snare rabbits in the area without success made the women feel almost superstitious about their good luck. They went back to the camp feeling lighthearted about all that had been accomplished.

That night the women talked about their plans. They agreed that they could not remain in the fall camp where they had been abandoned, for there were not enough animals on which to survive the long winter. They also were afraid that potential enemies might come upon them. Other bands were traveling, too, even in the cold winter, and the women did not want to be exposed to such dangers. They also began to fear their own people because of the broken trust. The two women decided they must move on, fearing that the cold weather would force people to do desperate things to survive, remembering the taboo stories handed down for generations about how some had turned into cannibals to survive.

The two women sat in the shelter, thinking about where to go. Suddenly Ch’idzigyaak burst out, “I know of a place!”

“Where?” Sa’ asked in an excited voice.

“Do you remember the place where we fished long ago? The creek where the fish were so abundant that we had to build many caches to dry them?” The younger woman searched her memory for a moment, and vaguely the place came to mind. “Yes, I do remember. But why did we not ever return?” she asked. Ch’idzigyaak shrugged. She did not know either.

“Maybe The People forgot that place existed,” she ventured.

Whatever the reason, the two women agreed that it would be a good place to go now and since it was a long distance, they should leave at once. The women yearned to be as far away as possible from this place of bad memories.

The following morning they packed. Their caribou skins served many purposes. That day, they served as pulling sleds. Taking the two skins off the tent frame, the women laid the skins flat with the fur facing the snow. They packed their possessions neatly in the skins and laced them tightly shut with long strips of babiche. They fastened long woven ropes of mooseskin leather onto the front of the skin sleds, and each woman tied a rope around her waist. With the fur of the caribou hides sliding lightly across the dry, deep snow and the women’s snowshoes making the walking easier, the two women began their long journey.

Temperatures had dropped, and the cold air made the women’s eyes sting. Time and time again, they had to warm their faces with their bare hands, and they continually wiped tears from their irritated eyes. But their fur and skin clothing served them well, for cold as it was, their bodies remained warm.

The women walked late into the night. They had not gone too far, but both were bone-weary and felt as though they had been walking forever. Deciding to camp, the women dug deep pits in the snow and filled them with spruce boughs. Then they built a small campfire, reboiling the squirrel meat and drinking its broth. They were so tired they soon fell asleep. This time they did not moan or twitch but slept deep and soundlessly.

Morning arrived, and the women awoke to the deep cold surrounding them while the sky above seemed like a bowl of stars. But as the women tried to climb out of their pits, their bodies would not move. Looking into each other’s eyes, the women realized they had pushed their bodies beyond their physical endurance. Finally, the younger, more determined Sa’ managed to move. But the pain was so great that she let out an agonized groan. Knowing this would happen to her, too, Ch’idzigyaak lay still for a while, gathering courage to withstand the pain she knew would come. Finally, she, too, made her way slowly and painfully out of the snow shelter, and the women limped around the camp to loosen their stiff joints. After they chewed on the remaining squirrel meat, they continued their journey, slowly pulling their laden toboggans.

That day would be remembered as one of the longest and hardest of the days to come. They stumbled numbly on, many times falling down into the snow from sheer fatigue and old age. Yet they pushed on, almost in desperation, knowing that each step brought them nearer to their destination.

The distant sunlight that appeared for a short while each day peeped hazily through the ice fog that hung in the air. Now and again, blue skies could be seen, but mostly the women noticed only their own frosty breath coming in thick swirls. Freezing their lungs was another worry, and they took care not to work too hard in the cold and, if such work was unavoidable, they wore a protec

tive covering over their faces. This could cause irritating side effects, such as frost buildup where the covering brushed against their faces. However, the women did not notice such minor discomforts compared with their aching limbs, stiff joints, and swollen feet. Sometimes even the heavy sleds seemed to serve a purpose by keeping the women from falling flat on their faces as they pulled onward with the ropes wrapped around their chests.

As the few hours of daylight slipped away, the women’s eyes readjusted to the darkness that began to enfold them. But they knew that night had not yet arrived and that there was still time to move. When it became time to camp, the women found themselves on a large lake. They could see the outline of trees along the shore and they knew that the forest would be a better place to camp. But they were so exhausted they could go no farther. Again they dug a deep pit in the snow, and after snuggling down and covering themselves with their skin blankets they were soon asleep. The thick skin and fur clothing held their body heat and protected them from the cold air. The snow pit was as warm as any shelter aboveground, so the women slept, mindless of freezing temperatures that made even the most ferocious northern animals seek shelter.

The next morning, Sa’ awoke first. The long sleep and cold air cleared her mind considerably. With a twisting grimace she stuck her head out of the hole to look around. She saw the outline of trees on the shore and remembered how they had been too tired to complete their crossing of the lake.

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival

Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival